| Forest carbon credits could help development in Congo: Interview with Nadine Laporte, remote sensing expert Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com May 28, 2008

Dr. Nadine Laporte, an associate scientist with WHRC who uses remote sensing to analyze land use change in Africa, says that REDD could protect forests, safeguard biodiversity, and improve rural livelihoods in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and other Central African nations. "REDD is perhaps the most promising way to protect forests in much of the tropics, including all the central African countries," Laporte told mongabay.com. "Carbon credits represent the largest potential flow of revenue to support sustainable development in tropical forest regions, particularly because most of the ecological services provided by these ecosystems (biodiversity, hydrology, sustenance of forest peoples, etc) do not have strong mechanisms to promote their conservation."

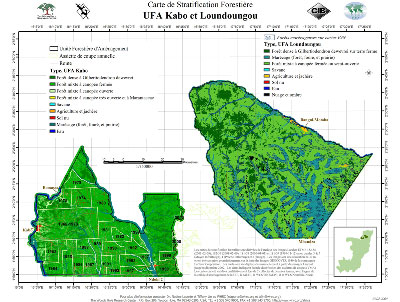

"It is necessary to reinforce national capacity to monitor forests and identify the best alternatives to reduce degradation and deforestation, despite wide variation between regions and types of land use," she said. "Moreover, most people in the DRC, for example, rely on fuel wood for their energy needs. As such, it is important to develop REDD programs in synergy with the forest, agriculture and energy sectors." Laporte says that remote sensing can help the effort by identifying where and why deforestation is occurring; the suitability of land for different types of uses including agriculture; and the carbon stocks of forests. Recently Laporte has used satellite imagery to map the potential for REDD and assess the extent of logging roads in some of the most remote parts of the Congo Basin. In conjunction with the remote sensing, Laporte also works on the ground, training people in central African countries to use satellite remote sensing for forest mapping and monitoring. She engages a wide range of stakeholders including scientists, conservation groups, government forestry departments, forest peoples, and logging firms. Laporte discussed these projects and more in a May 2008 interview with mongabay.com. Mongabay: What is your area of research?

Mongabay: Is most of your work done in the field, via remote sensing, or a combination of the two?

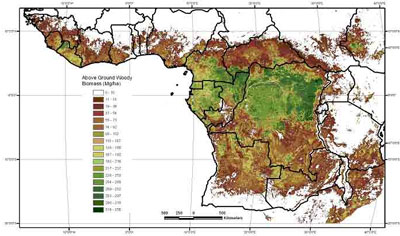

Nadine Laporte: My group uses a combination of satellite imagery integrated with field information. We rely on field information for the calibration of our models and also for the validation of our results. To produce our maps of the distribution of above-ground biomass of tropical Africa, for example, we collected field information from foresters and national institutions. In the Republic of Congo some of our remote sensing analyses have been used to develop national mapping standards for forest management plans. In the DRC our biomass map was used to calculate the level of compensation necessary reduce emissions from deforestation. Mongabay: How did you become involved in the work you do today? Nadine Laporte: I studied tropical biology in Toulouse France, when the French space program was just getting started. Using satellite imagery for monitoring tropical forests appeared to me an ideal area of applied research, and I decided to study forests from space. Remote sensing was not taught at the University (Paul Sabatier) yet, but I was able to get an internship in the Laboratory for International Mapping run by a Professor Blasco. At the time they had one computer as large a Fiat and I started learning the basics of satellite remote sensing analysis. I have always been fascinated with tropical forests, and working on better forest conservation and management has become ever more critical as conversion to crops and pasture continues to increase in most tropical countries. Mongabay: Given the state of infrastructure in DR Congo, is remote sensing an effective way to monitor remote parks in the country? What can remote sensing tell you beyond the extent of forest cover?

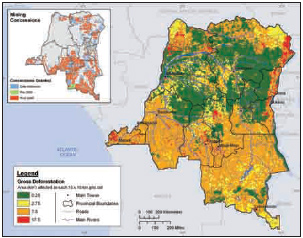

Mongabay: You recently completed a preliminary assessment for the potential of REDD in DR Congo. Can you highlight some of your findings? Nadine Laporte: We found that more than 17 billion metric tons of carbon are stored in above-ground biomass across the DRC. During the period 1990-2000, the annual CO2 emissions from deforestation were estimated to be 226 million tons. Some of this carbon is not immediately released to the atmosphere but remains as dead wood or as wood products removed from the forest, both of which have slower decay and emission rates. We estimated that for a 50 percent reduction in carbon emissions, total rural household compensation would likely range between $120 million to $400 million per year for 10 years, depending on the level of compensation required (i.e. between $300 and $1000 per household per year). The mean carbon price to accomplish this compensation would range from $19 to $65 per ton with, importantly, more than 30 million tons of carbon available to the carbon markets for less than $10 per ton. Carbon credits represent the largest potential flow of revenue to support sustainable development in tropical forest regions, particularly because most of the ecological services provided by these ecosystems (biodiversity, hydrology, sustenance of forest peoples, etc) do not have strong mechanisms to promote their conservation. In the DRC, we are focusing on building capacity in the government and with civil society to take advantage of this new mechanism. Mongabay: Do you see REDD as a viable form of land use in DR Congo for the future? Will REDD be a good way to protect forests in the region?

Mongabay: Beyond REDD, do you recommend other ways to protect forests and wildlife in DR Congo

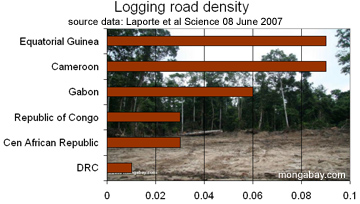

Mongabay: You have published some interesting research on the role of logging roads on market hunting in the Congo Basin. Is logging likely to continue being a driver of poaching in the region? Will logging roads facilitate the development of agro industry in forest areas?

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students wishing to follow in your footsteps? Nadine Laporte: I would recommend students to volunteer in research labs and various projects in the tropics. The need has never been more urgent or the timing more critical. We have only one blue planet - and who wants to live on Mars? Mongabay: What is your favorite place in the tropics? Nadine Laporte: I don't have any particular favorite - there are many places that are unique and special in their own way, and each contributes to the diversity of life and cultures in Central Africa. |

--

Jean-Louis Kayitenkore

Procurement Consultant

Gsm: +250-08470205

Home: +250-55104140

P.O. Box 3867

Kigali-Rwanda

East Africa

Blog: http://www.cepgl.blogspot.com

Skype ID : Kayisa66

No comments:

Post a Comment