Living without 'isms'

'It's in literature that true life can be found. It's under the mask of fiction that you can tell the truth'

- The Guardian,

- Saturday August 2 2008

- Article history

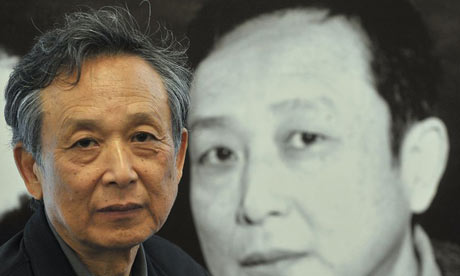

Gao Xingjian. Photograph: Mike Clarke/AFP/Getty

In May this year, when news of the Sichuan earthquake reached the Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian at his home in Paris, he remembered living through a similar disaster in China more than 30 years ago: "Even though I was quite far away then, I was terrified." That earthquake, in Tangshan, near Beijing, was one of the 20th century's worst in terms of lives lost. "Afterwards there were terrible downpours, but no one wanted to stay in the buildings. I can imagine the fear in Sichuan."

It was the tail-end of the cultural revolution, the collapse of which was accelerated by the aftermath of the 1976 quake. When the 10-year terror began in 1966, Gao felt compelled to burn a suitcase-full of all his manuscripts since adolescence, in case he was denounced. But he was still sent for "re-education" in the countryside. Labouring in the fields, he began again, hiding his work in a hole in the ground, when "to write, even in secret, was to risk one's life". As Gao said in 2000 when he became the first (and only) writer in Chinese to win the Nobel prize for literature, "it was only during this period, when literature became utterly impossible, that I came to comprehend why it was so essential."

Gao, who was first published when he was almost 40, has written more than 20 plays, short stories, essays, criticism and two semi-autobiographical novels: Soul Mountain (1990), based on a journey down the Yangtse river; and One Man's Bible (1999), memories of the cultural revolution spliced with episodes in the life and loves of a world-famous man of the theatre. The novels were translated into English in 2000 and 2002, followed by Buying a Fishing Rod for My Grandfather (2004), a collection of short stories. His Nobel lecture is the title essay of The Case for Literature (2007). Yet since 1989 all his work has been banned in mainland China (most has been published in Taiwan).

A pioneer of experimental theatre in China in the early 1980s, Gao fell foul of renewed purges, and left for Germany, then France in 1987. But it was his reaction to the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 that he believes sealed his fate. "I heard the news on the radio that people were gunned down, and right then, I knew I was looking at exile," he says. He condemned the crackdown on French television, publicly resigned from the Chinese Communist party he had joined in 1962, tore up his Chinese passport and applied for political asylum. He has lived in Paris for 21 years as a painter and writer/director, becoming a French citizen in 1998.

For Jung Chang, Gao has "immortalised the memories of a nation suffering from forced amnesia; my own memories flooded back reading him". Ma Jian, the London-based author of Beijing Coma, sees Gao as "both a linguistic innovator and a writer of integrity, whose work constantly reaffirms the importance of the individual over the collective. He was one of the first writers of the post-Mao era to absorb developments in western literature and philosophy, and meld them with Chinese classical traditions to create a new kind of drama and fiction." By contrast, the critic Julia Lovell commends his shorter fiction yet feels the novels are a "sprawling, self-indulgent take on the horrors of political oppression".

Aged 68, Gao lives in Paris's 2nd arrondissement with Céline Yang, a novelist who left China after 1989. Gao, who also writes in French, has translated and directed plays in his adopted language, and was awarded the Légion d'honneur in 2000. He sees himself as a "fragile man who has managed not to be crushed by authority and to speak to the world in his own voice". As he pointed out recently at Warwick University, on a rare visit to Britain, most of his life's work has been done since leaving China. While the Swedish academy saw him as a "perspicacious sceptic" possessed of "bitter insights", for Ma, Gao is a "tranquil yet engaged presence; a very composed, mild-mannered man, but a passionate reader and artist". Speaking in French, smiling readily though he seems frail, Gao recalls the Nobel prize as a "whirlwind. I was carried away, and it was difficult to organise my life. Very soon after, I fell ill, and had two big heart operations one after the other. It was because of the fatigue and pressure. I became an ornament on the political scene."

The official Chinese reaction to the Nobel was predictably hostile. The head of the Chinese Writers' Association said the prize had been "used for political purposes and thus has lost its authority". According to Ma, that body had "campaigned for years for the Nobel prize to be awarded to one of their state-sanctioned writers, so they were furious when it went to a political exile". Yet Gao has also been attacked by dissidents - notably for his play Escape (1989), written within months of the Tiananmen Square massacre, and the ostensible trigger for all his work being banned in China. Its three characters take refuge from the army crackdown in a warehouse, amid sexual tensions and cynicism about self-proclaimed heroes. "Exiled writers said my play blackened the democracy movement," Gao says. "Even today, those attacks continue." In Ma's view, "It was criticised by the pro-democracy activists because it failed to show the students in a heroic light."

According to Gao, a writer's only responsibility is "to the language he writes in". Determined to rid himself of others' ideologies, to live, as he says, "without isms", he advocates a "cold literature", detached from both political agendas and consumerist pressures, whose purpose is to bear witness. His essays express a loathing for Nietzsche's idea of the Superman and and its hold over Chinese thought. "Many intellectuals feel themselves to be Supermen who are spokesmen for the people," he says. "But in my opinion, they're to be pitied. Under Mao's dictatorship, these poor sheep suffered the same fate as everyone else. I don't want to be a strong hero who can save society. I just want to save myself."

He was born in 1940, the eldest of two brothers, in Ganzhou. Shortly after the Communist revolution of 1949, the family moved to Nanjing. His father was a senior employee in the Bank of China, and his mother an amateur actor. It was a "well-to-do, protected childhood, and my parents were very open-minded - which was rare. It's like a lost paradise." His mother read western literature in translation, from Balzac and Zola to Steinbeck, and he grew up with both western and Chinese classics. His love of theatre comes from his mother, with whom he first acted on stage, aged five. She also encouraged him to keep a diary. But when Gao was 20, during the "great leap forward", she drowned at a rural labour camp. "Even though she wasn't really an intellectual, she was sent away for re-education just like all the others who were not from Communist 'red' families," he says.

As a child he played the violin and flute, and painted, but opted to study French literature at the Beijing Foreign Languages Institute, drawn to such dramatists as Genet and Artaud. After graduating in 1962, he worked at the Foreign Languages Press, translating French classics. But in 1966-76, all foreign-language books were banned.

In One Man's Bible, the narrator is both participant in the cultural revolution and victim. After protesting against Red Guards' beating of a colleague at his workplace, Gao was treated as a hero, and led a rival Red Guard faction. The Red Guard, he explains, was initially composed of "children of high-up party executives, who felt like mowing down and killing old people like their parents. Other youths reacted and set up a rebellious Red Guard faction. All young people, to protect themselves, had to join one or the other. But once I got in, I saw it wasn't really a way out. Experience has taught me that any kind of political grouping is oppressive. It's the blind mass that crushes the individual."

The novel also reflects Gao's experience of being informed on by his first wife. On this he will say nothing, other than to allude to Stalinist Russia and East Germany. After Mao's death in 1976, Gao translated Beckett and Ionesco, and visited France and Italy. In his first book, essays on the modern novel, he took issue with Mao's guidelines for literature urging didactic, realist art. In Ma's view, the book "influenced a generation of writers by introducing them to the concepts of stream of consciousness, surrealism and black humour." Gao, Ma adds, was "the 'elder brother' of the small band of dissident Beijing artists and writers that I belonged to. He could speak foreign languages and had travelled abroad. We all looked up to him."

Made artistic director of the People's Art Theatre in Beijing in 1981, Gao broke with realism in experimental plays such as Absolute Signal (1982), about the change of heart of a would-be train robber. It startled Ma by exploring, "in a nuanced way, the psychology of a 'bad' individual. It heralded a new kind of drama, in opposition to the one-dimensional propaganda of the cultural revolution". Yet Gao became an early casualty of a renewed drive in 1983 against "spiritual pollution" and western modernism. His play Bus Stop (1983), a take on Waiting for Godot, was banned after 10 performances.

"I'd already self-censored," Gao says. "Then I was censored by others. That's when I decided to write just for myself." His resolve coincided with being diagnosed with lung cancer - the disease from which his father had died. "After Bus Stop, they threatened to send me back to work camp. Then this shadow was found on my lungs. I went back to my hometown and had more tests - and by a miracle it had disappeared." The reprieve made him realise that "if you want to do anything, do it now, without compromise or concession, because you have only one life."

He fled to the forest highlands of south-west China, ostensibly to research woodcutters' lives. For five months he tracked the Yangtse riverfrom its source, from Sichuan's giant panda reserve to the China sea. "I was looking for a place of refuge. It was also a spiritual and cultural quest, to find the origin of Chinese culture, the source that had not yet been polluted by politics." The result, completed in Paris after more of his plays had been banned in rehearsal in Beijing, was Soul Mountain, which took seven years to write.

The novelist and film-maker Xiaolu Guo read a pirated copy and found it "very beautiful and poetic - intimate but epic". "The novel in Chinese sensibility is 2,000 years old," she says. "It's the language of real people from the streets - the non-official version." For Gao, the "tiny history of a few individuals in a novel can't be revised or manipulated. It goes to the heart of human nature. If it's still read, it's still valuable."

Though it reads like an autobiographical monologue, Soul Mountain shifts viewpoints - a technique repeated in One Man's Bible and Gao's plays. "Literature can't merely be an expression of self - that would be unbearable," Gao says. "You have to be critical not just of society and others, but of yourself: each subject has three pronouns: 'I', 'you', and 'he' or 'she'." He sees such self-scrutiny as a safeguard: "If you're not perfectly conscious of yourself, that self can be tyrannical; in relationship to others, anyone can become a tyrant. That's why no one can be a Superman. You have to go beyond yourself with a 'third eye' - self-awareness - because the one thing you cannot flee is yourself. That's why Greek tragedy is still the tragedy of human beings today."

Gao's later plays have been called a modern Zen theatre, combining modernist techniques with traditional Chinese drama and ritual, from masks and shadow play to opera. They have been widely staged in Europe, Taiwan and Hong Kong - where Tales of Mountains and Seas (1993) premiered in June at a festival devoted to Gao's work. But they are rarely seen in the English-speaking world. Escape was commissioned by a US theatre company, but premiered in Sweden after Gao refused to revise it. "When the company asked me to change the text, I understood what they wanted: there was no American-style hero," he says. "I said, no. Even the Chinese Communist party couldn't make me change a play; why should I accept correction from America?"

It was while directing his modern take on a Peking opera, Snow in August (2002), in Taiwan, that Gao collapsed and later had major heart surgery. In Marseilles rehearsing his play The Man Who Questions Death (2003), he collapsed again. He has co-directed a 90-minute film, Silhouette/Shadow (2006), that reflects his brush with death. Showing him painting, reciting poetry and rehearsing actors, it captures a flow of images and memories as he is rushed to hospital in an ambulance. A "cinepoem or modern fable - neither fiction nor autobiography nor documentary", it was filmed over four years, without funding. "Since childhood I'd dreamed of making a film, but producers in France and Germany wanted to make commercial films with chinoiserie. I refused."

The film, which has no dialogue and might be released only on the internet, is part of a life's experimentation.Though he enjoys dancing, swimming in the sea and cooking seafood, Gao says he works "non-stop, 12 hours a day", and never takes summer holidays "or even weekends, because freedom of expression is so precious to me".

The market pressures China now shares with the west are, he believes, "harder to resist than political and social customs". He feels lucky that his ink paintings were selling in Europe before he fled, and have been widely exhibited. "I could make a living, so I could write books that didn't sell much. I always understood that literature can't be a trade; it's a choice." Painting, he says, "begins where language fails", and he works listening to music - often Bach. Ma sees his paintings as "infused with the still, reflective quality of Zen Buddhism that I think he strives to achieve in his writing."

To Ma, who believes that One Man's Bible is about the "burden of painful memories, and how they corrupt the present and destroy oneself and those around one", it is a "tragedy that a writer of such calibre is condemned in his own homeland". Guo feels Gao's voice is crucial for its "stubborn, personal view of our history. The kids born after the 1980s know nothing about the past - the tragedy and sorrow of my father's generation - and how society dedicated to a collective dream ruined people and invaded their lives."

Gao sees his work as an affirmation of the self in the face of efforts to extinguish it. Recalling a time when it was "impossible to say freely what you thought, even in your family", he says: "Everything people say in those circumstances is false; everybody is wearing a mask. It's in literature that true life can be found. It's under the mask of fiction that you can tell the truth."

Gao on Gao

"Without Isms is neither nihilism nor eclecticism; nor is it egotism or solipsism. It opposes totalitarian dictatorship but also opposes the inflation of the self to God or Superman. It hates seeing other people trampled on like dog shit. Without Isms detests politics and does not take part in politics, but is not opposed to other people who do. If people want to get involved in politics, let them go right ahead. What Without Isms opposes is the foisting of a particular brand of politics on to the individual by means of abstract collective names such as 'the people', 'the race' or 'the nation'."

(The idea behind it is that we need to bid goodbye to the 20th century, and to put a big question mark over those "isms" that dominated it.)

· From The Case for Literature, translated by Mabel Lee, published by Yale University Press

--

Jean-Louis Kayitenkore

Procurement Consultant

Gsm: +250-08470205

Home: +250-55104140

P.O. Box 3867

Kigali-Rwanda

East Africa

Blog: http://www.cepgl.blogspot.com

Skype ID : Kayisa66

No comments:

Post a Comment