One big act

Tyrant, romantic, hypochondriac, slacker - Jean-Luc Godard has played an astonishing array of roles both away from and behind the camera. His greatness is not in doubt, says Chris Petit, but are his films any good?

- The Guardian,

- Saturday August 9 2008

- Article history

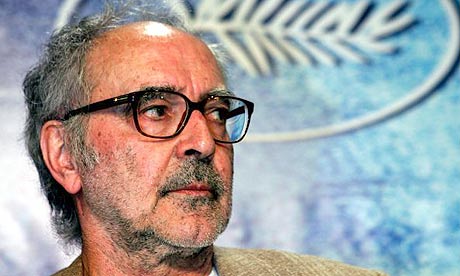

'The important thing is to be aware that one exists' ... Jean-Luc Godard. Photo: Vincent Kessler/Reuters

Godard wrote his own epitaph early, in Alphaville (1965): "You will suffer a fate worse than death. You will become a legend." There is no bigger personality cult in terms of film director as artist, and Godard has always been an assiduous curator, understanding the need, as Warhol did, of making a spectacle of himself. But while professing openness he remains opaque and, in a sense, the film-maker known as Jean-Luc Godard may not exist, any more than the musician known as Bob Dylan does, except as several simulacra. For this reason, the scattered asides in Richard Brody's exhaustive new biography, Everything is Cinema, perform the book's most useful task, catching the less canny, unguarded Godard.

- Everything is Cinema

- by Richard Brody

- Faber,

- £30

He suffers from vertigo (how appropriate). He admits to having no imagination and taking everything from life. When he was given a camera to use by film-maker Don Pennebaker, Pennebaker was touched by his incompetence, which included the beginner's mistake of zooming in and out too much. He was introduced to the fleshpots of Paris in the 1950s by an early mentor, film director Jean-Pierre Melville. Financial transactions with prostitutes were treated as potential mises en scène (Vivre sa vie, Sauve qui peut); cinema as whore. His handwriting features in many of his films; ditto his voice. He plays tennis, or did (he's nearly 80 now). When he passed on production money from a film to Italian revolutionaries, they used it to open a transvestite bar. He smoked a fat version of Gitanes called Boyards. In his Marxist days, he still travelled first class. He tried to avoid writing scripts whenever possible. His once great friend François Truffaut called him "the Ursula Andress" of the revolutionary movement. He is Protestant in temperament and an unforgiving moralist. He drops names. He lay in a coma for a week after a motorcycle accident. He can be nasty. He has been known to suffer hopeless crushes. In late adolescence he was committed by his father into psychiatric care. His on-set tantrums are legendary. He is the Saint Simeon Stylites of cinema, atop his pillar, or, as Truffaut described him, nothing but a piece of shit on a pedestal. For all his utopian ideals, conflict and rejection are the dominant impulses of his life and work.

In A Biographical Dictionary of the Cinema, David Thomson has Godard emerge from the darkness of the Cinémathèque rather than any plausible biographical background. Brody restores the biography and takes the life and work in order - not necessarily the most rewarding way of approaching a subject who has declared that films require a beginning, middle and end, but not necessarily in that order.

The facts are plain enough. Godard was born in 1930 into a rich, prestigious Swiss-French Protestant family, against whom he rebelled by turning to cinema and falling in with a like-minded crowd. In these days of image-glut, it is hard to imagine a fanatical coterie taking film so seriously. This was partly to do with catching up, after the German occupation, on previously unavailable Hollywood films; partly fashionable existentialism. Writing in Cahiers du cinema, these young filmmakers-in-waiting found moral codes in the work of men such as Howard Hawks and Hitchcock, and began to identify films by directorial signature. Steeping themselves in US cinema was also a way of sidestepping politics and the embarrassment of France's wartime collaboration (members of Godard's family had sided with Vichy France and Godard himself could be provocatively pro-German).

Godard's criticism was a mix of hyper-enthusiasm, vicious sniping, fawning and name-dropping, with cinema regarded as a matter of life and death. It also offered an obvious direction: "When we saw some movies we were finally delivered from the terror of writing. We were no longer crushed by the spectre of the great writers." He and his friends wrote their way into films via Cahiers du cinema. Photographs of the Cahiers crowd show straight young men in suits, looking like apprentice bankers, a rightwing bunch whose real target was the stuffy, inflexible French film establishment. As Godard put it: "We barged into cinema like cavemen into the Versailles of Louis XIV." He watched colleagues and rivals, Claude Chabrol and Truffaut, get their features made first. He stole from his family to finance Jacques Rivette. Of the Godard family he has said approvingly that they were like foxes. The same was said, disparagingly, of him and his business practices; he liked deals with a bit of a kick to them. In a way, his artistic career can be read in terms of what he would steal or scavenge by way of reference - the magpie thief.

Godard's first feature, À bout de souffle (1960), was from a back-of-an-envelope sketch by Truffaut, and most of those involved, including the leads, were sure they were making a dog. Its success now looks like a combination of fluke - a long-odds bet by Godard on his own talent, which paid off - and something willed. On the one hand, he trusted his saturation in cinema to guide him. On the other, he pushed what he was doing to the limits. Not everyone was charmed by the result, but Godard was lucky with his lead, Jean-Paul Belmondo, who did charm and whose sinuous athleticism drives the film.

Godard also ripped up the rule book, brattishly challenging the notion that cinema needed to be a polite and conformist medium in pursuit of an illusion of reality. The most pertinent critical comment was that À bout de souffle made Truffaut's Les 400 coups (1959) look like an obedient schoolboy's homework, and Chabrol's films the product of a perfect academicism. Godard was also a brilliant publicist, with an adman's talent for reducing ideas to captions. His two great riffs were the impossibility of love, and death. He charged on, working cheap, careering between success and failure. Les Carabiniers (1963) was a spectacular flop. When his future collaborator Jean-Pierre Gorin went to see it, the cinema refused to show it unless someone else turned up. Godard was restless, not given to repetition: he reworked the gangster film, musicals, science fiction, changing styles as he went along. The notorious jump cuts that were his signature in À bout de souffle were little used again.

But false premise (and promise) became a recurring motif in a career sustained less by its triumphs than by cul-de-sacs, professional crises and personal breakdowns, many self-inflicted as a way of inducing an artistic response. "Breathless" applies to his initial, prolific output of 15 features in seven years, until he ran out of steam and threw himself into Maoist dogma with the same blind vigour and instinct for the zeitgeist. It seemed a remarkable volte-face for a man whose early political views had been described as virtually fascist, but he was really only swapping one authoritarian form for another. He acquired a student wife (his second, Anne Wiazemsky, whose attraction was having played the lead in Robert Bresson's Au hasard Balthazar of 1966) and a collaborator, Gorin, whose radical influence helped him realise greater autonomy on his return to production proper, with the repentant Sauve qui peut (1980). The revolutionary phase now seems less Maoist than Lennonist; Gorin declared at the time, "I am the Yoko Ono of cinema." Then as now, politics seemed to be one part of a more complex personal agenda. Even an ostensibly political film from the first period such as Le Petit soldat (1963), about an extreme-right death squad in the Algerian conflict, views more like a Swiss holiday (shot in Geneva to avoid French censorship) and love letter to Anna Karina, who would become his first wife, in their first film together.

The surprise in Brody's account is the thoroughness with which Godard strip-mined his life to feed the films. The opening marital row in Vivre sa vie (1962), prompted by a confession of infidelity by a wife (Karina), sounds so raw it could have been a rehash of the previous night's argument, provoked by Godard for the sake of the scene. In a cinematic version of Stockholm syndrome, Karina remained a prisoner in his films long after their marriage was over. Their psychosexual dynamic probably finds its most accurate summary not in something written about them at all, but in Terence Blacker's biography of Willie Donaldson, You Cannot Live As I Have Lived and Not End Up Like This: "She sensed that what really excited him was sexual jealousy and . . . was prepared to go as far as he wanted, taunting him, betraying him with other men and then returning to face his ecstatic rage."

The real reason for Godard's bust-up with Truffaut was because Truffaut was more successful at seducing actresses. But in Truffaut's films an actress, had by him or not, remains an actress, where in Godard's hands Karina became transcendent, thereby making herself redundant (her career barely survived Godard). Few have appeared more exposed by the camera, flayed even. In Vivre sa vie she was cast as a prostitute while Godard, salacious and prudish, Nosferatu and pimp, remained reluctant to share her and expected her at all times to be well-mannered and demure.

Just as Godard has played with cinema, he has constructed multiple versions of himself before and behind the camera, leasing out the character of JLG to actors and sometimes acting himself: cinephile, tyrant, tardy, silver-tongued, Professor Pluggy, politico, foxy businessman, smutty Uncle Jean, fraud (a history of youthful theft), romantic, classicist, dandy, hypochondriac and slacker. A cold reading of the man suggests hysteric, obsessive, depressive, leavened by the schoolboy who was remembered for playing the fool. An early collaborator told me they fell out because "He's a liar and, what's more, he knows I know he is a liar!" "Je suis un con," Belmondo says at the beginning of À bout de souffle, a clear enough mission statement for the general cinematic conduct to follow and the recurring, underlying question of how much of a shit is it necessary to be in life and film.

Godard eventually swapped a private life with actresses for one with a director, Anne-Marie Miéville, under whose stern eye he appeared in two features as a man racked by jealousy, bookish, remote, endlessly bickering and so berated by his partner (played by her) that, in another variation of the Stockholm syndrome, with the boot on the other foot now, he is the one who breaks down, sobbing; jailer turned captive.

"Film is a battleground," said US director Sam Fuller in his cameo in Pierrot le fou (1965), which was shot by Godard's regular cameraman Raoul Coutard - tough, fast and a veteran of the battle of Dien Bien Phu. Whether by fluke, design or incompetence, Godard the genius and Coutard the hero set their own rhythm from the start, Godard writing on location with cast and crew waiting. Using little or no additional lighting, they learned to push stock exposures to the limit (there were thousands of feet of night shooting on Alphaville). Conditions permitting, they dumped lighting, tracks, sync sound, hair and makeup and, above all, continuity, shooting as much as possible on the hoof - and if anyone looked at the camera, so what.

Characteristic of the method, usually to do with running over budget, was a loose series of scenes followed by an incredibly long one, shot fast in a single space in extended takes, in an effort to recoup costs, during which a man and woman fail to resolve their relationship. What Godard had grasped was that film didn't have to pretend to be real.

He admitted his laziness shooting À bout de souffle, the clever slacker who gets by on reading the first and last page of a book. Elia Kazan, visiting the set of Vivre sa vie, was uncomprehending when told that Godard never shot a scene from more than one angle. Melville, a more classic and scrupulous director than Godard, criticised his sloppiness, as a result of which their friendship ended.

Coutard told a fellow crew member on Alphaville that what Godard would really like would be "to swallow the film whole and process it out his ass - that way he wouldn't need anybody". Given that his creative process is to manipulate everything, himself included, it is tempting to brand Godard as a sophisticated high-class soap, a product based on a tailored understanding of market and media. As his audience diminishes, his reputation is enhanced through careful cultivation of, and endorsement by, art establishments and academia. Once ahead of his time, embracing new technology (video) and surfing the zeitgeist as someone might browse the internet, he now denounces digital as death and takes refuge in history, in anticipation of posterity's judgment.

Talking about Luchino Visconti's Senso (1954), Godard said: "Each time, I want to know what Farley Granger says to Alida Valli, bang! - fade out." The same is true of Brody, and often one wants more than what's offered - on the French intellectual climate in general (he remains much more comfortable with American responses to Godard) and, given Godard's animosity, on established feuds. Brody also fails to mention his own snubbing when in Switzerland in 2000 to profile Godard for the New Yorker. In a typical Godardian move, the director terminated the interview by note, blaming Brody for being vague and unfocused, which was the last thing he probably was. Also typical, Godard and Miéville, a scary pair at best, made a point of dining at Brody's hotel that evening and blanking him.

Godard remains stubbornly silent about the darkness surrounding many relationships. He describes his childhood as idyllic, which is disingenuous when the career is so full of acts of surrogate patricide, and what would a shrink make of one of the first lines of À bout de souffle, when Godard's surrogate sings "Pa-Pa-Patricia!"? The disturbed adolescence, the stealing, suicidal tendencies, the committal for psychiatric inspection, a period that lasted some months - none is adequately explained. Nor is the effect of his parents' break-up around the same time and his mother's death two years later in a road accident. Nor are his unexplained absences, Karina's and his unborn child, her suicide attempts, let alone his return from the dead, or how they all fed into the films.

Godard has remained prolific, if less seen. There are more than 100 credits altogether, but since the mid-1980s the films have been harder to see, as audience and critical interest dwindled and distribution became erratic. Brody considers Sauve qui peut Godard's second great "first" film, but if memory serves, an earlier return with Numéro Deux (1975) was bolder in its use of film and video, and its analysis of family life, grubby ordinariness, sexual economics and the relentlessness of male desire.

With age, Godard came to regard cinema, which he had once taken for his secular bible, in increasingly biblical terms, its fall marked by the rupture of the second world war and cinema's failure to record the Holocaust as it happened. He turned on Hollywood, particularly Steven Spielberg. His later work is self-consciously that of a crabby iconoclast and old master. In Éloge de l'amour (2001), the black and white stock is treated with a painterly reverence worthy of Rembrandt, the pellicule or grain of the film as important to the character of the piece as the story (which is deliberately fractured) or movement of the actors. Despite Brody's exhaustive shot synopsis, the film remains elusive because Godard resists conventional summary: it is a question of textures and associations, animated by his knowledge that a form of cinema understood by him (35mm black and white) has become redundant. Focus in Godard has always been on what remains unsaid and spatial distance, particularly that between the audience and the screen. I often switch off to what the films are about, entranced instead by the abstract interplay of elements and the astonishing achievement of taking an industrial process and fooling around with it like it were miniDV.

Cinema comes down to something shown. Godard said as much in 1965: "The important thing is to be aware that one exists. For three-quarters of the time during the day one forgets this truth, which surges up again as you look at houses or a red light, and you have the sensation of existing in that moment." He repeated the point years later with reference to Hitchcock: "We forget why Janet Leigh stops at the Bates motel . . . what Henry Fonda was not entirely guilty of and exactly why the American government hired Ingrid Bergman. But we remember a glass of milk, the blades of a windmill, a hairbrush."

Subscribing to Godard, it is hard not to develop a personal and argumentative relationship, and watching any Godard is a more subjective experience than viewing, say, Carol Reed's The Third Man. Because the films rarely offer more than perfunctory closure, cartoonish even in death, they remain open, functioning more like books. Godard spans cinema, being of a generation that grew up with and followed its arc, and in his Swiss-Protestant way he was its Reformation. Brody's linear approach pays off in showing how Godard has in effect been making one big film, a life's work and a reference map of cinema. But one unanswered question remains: we know he was great, but was he any good?

--

Jean-Louis Kayitenkore

Procurement Consultant

Gsm: +250-08470205

Home: +250-55104140

P.O. Box 3867

Kigali-Rwanda

East Africa

Blog: http://www.cepgl.blogspot.com

Skype ID : Kayisa66

No comments:

Post a Comment